Fifty original leaves from medieval manuscripts

Pages

-

-

Breviary (Breviarium)

-

Breviaries were seldom owned by laymen. They were service books and contained the Psalter with the versicles, responses, collects and lections for Sundays, weekdays, and saints' days. Other texts could be included. A Breviary, therefore, was lengthy and usually bulky in format. Miniature copies like the one represented by this leaf are rare. The angular gothic script required a skilled calligrapher. It would be difficult for a modern engrosser to match, even with steel pens, the exactness and sharpness of these letters formed with a quill by a 13th century scribe. Green was a decorative color added to the palette in the late 13th century in many scriptoria. The medieval formulae for making it from earth, flowers, berries, and metals are often elaborate and strange. This manuscript was written on fine uterine vellum, i. e., the skin of an unborn calf. It evidently had hard use, or may have been buried with its owner. France: Breviary. Illuminated. Late 13th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

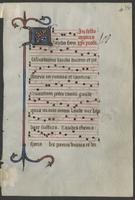

Breviary (Breviarium)

-

In the middle of the 14th century many of the manuscripts show influences from other countries. Illuminators, scribes, and other craftsmen traveled from city to city and even from country to country. While the script of this leaf is almost certainly French, the initial letters and filigree decoration might easily be of Italian workmanship, and the greenish tone of the ink suggests English manufacture. The dorsal motif in the bar ornament is again decidedly French, and the lemon tone of the gold is a third indication of French origin. In England, the burnished gold elements are generally of an orange tint, due to the presence of an alloy; in Italy, they are a rosy color because the underlying gesso or plaster base was mixed with a red pigment. France: Breviary. Illuminated. Middle 14th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Cambridge Bible (Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata)

-

The only Bible known to Western Europe for the thousand years from 400 to 1400 was this version by St. Jerome. In the early part of the 13th century it is almost impossible to distinguish the book hands of France from those of England. The decorative initials, color of ink, and texture of vellum are the clues which aid in assigning provenance, as in this instance. Not many fragments of this age and size are known to have survived the destruction and dispersal of English monastic libraries which was ordered by Henry VIII in the year 1539. This small size lettering, seven lines to the inch, is formed with the skill and precision that made the 13th century noted for the finest calligraphy of all time. To write seven lines to an inch, maintain evenness throughout, and have each letter clear and precise is a great achievement for any scribe, yet in the 13th century this was not an exceptional accomplishment. England (Cambridge): Cambridge Bible. Early 13th C. Latin text; early Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Dialogues of Gregory the Great (S. Gregorius Magnus, Dialogi)

-

This composite text includes the Dialogues of Pope Gregory I (St. Gregory the Great, 540-604 A.D.), which are largely autobiographical, and his writing on the lives and miracles of the early Italian Church Fathers. The book hand used is known as lettre Bátarde, a semi-cursive hand closely related to the everyday writing used by the people. Many French and Flemish printing types were based on similar Bátarde hands. The writing was done with comparative speed; the even tone and the exact alignment of the right hand margin, as well as the beauty of individual letters, are admirable. The long ascenders in the upper line were borrowed from the legal documents of the day. Many printers followed the practice shown here of emphasizing the tone of the first word or two in the beginning of a paragraph. It was usually done without varying the style of the letters, while here we see angular gothic used in the first third of the line, followed by the Bátarde script. France: Dialogues of Gregory the Great (S. Gregorius Magnus, Dialogi). Late 15th C. Latin text; Lettre Bátarde.

-

-

Epistolary (Epistolarium)

-

Epistolaries are among the rarest of liturgical manuscripts. Their text consists of the Epistles and Gospels with lessons from the Old Testament for particular occasions. Sometimes, as in this leaf, they had interlinear neumes in red to assist the deacon or sub-deacon in chanting parts of this section of the church service while he was standing on the second step in front of the altar. The text is written in well executed rotunda gothic script with bold Lombardic initials. Some of the filigree decoration which surrounds the initial letters has faded because it was executed in some of the fugitive colors which were then prepared from the juices of such flowers and plants as tumeric, saffron, lilies, and prugnameroli (buckthorn berries). Italy: Epistolary. Middle 15th C. Latin text; Rotunda or Round Gothic script; square rhetorical neumes.

-

-

Gradual (Graduale)

-

Graduals are the books containing the chants for the celebration of the mass. English manuscripts of this early date and small size are rare. This volume, with the uncertain strokes in the script, seems to indicate that the transcriber was unaccustomed to writing in this small scale. There are four and five line staves, and the "F" and "C" lines are indicated. Most of the various foms of written notes can be found on each leaf of this book. Thos occurring more frequently are punctum (L. 'punctum', prick), a single note; virga (L. 'virga', rod), a square note with a thin line attached; podatus (L. 'pes', foot), two square notes, one above the other; climacus (L. 'climax', ladder), a virga note with two or more diamond shaped notes. There are other forms for particular nuances of expression. There are more than 2,300 chants which have come down to us from the Middle Ages. The majority of these, however, can be reduced to a relatively few melodic types -- probably not exceeding fifty in all. England: Gradual. Early 13th C. Latin text; early Angular Gothic script; square Gregorian notation.

-

-

Gradual (Graduale)

-

A Gradual contains the appropriate antiphons of a mass sung by the choir of the Latin Church on Sundays and special holidays. The text was furnished largely by the 150 Psalms and the Canticles of the Old and New Testaments. The superb example of calligraphy in this leaf illustrates the supremacy of the Italian scribes of the time over those of the rest of Europe. It is frequently assumed that this late revival of fine writing may have been caused by the concern of scribes over the impending competition with the newly invented art of printing. The music staff still retains here the early 12th century form with the C-line colored yellow and the F-line red. The four-line red staff had been in use for over two centuries before this manuscript was written. Italy (Florence): Gradual. Illuminated. Middle 15th C. Latin text; Rotunda Gothic script; square notations.

-

-

Hymnal (Hymnaruim)

-

At important festival services such as Christmas and Easter these small hymnals were generally used by the laymen as they walked in procession to the various altars. Much of the material incorporated in the hymnals was based on folk melodies. Hymns, like the other chants of the Church, varied according to their place in the liturgy. Their melodies are frequently distinguished by a refrain which was sung at the beginning and at the end of each stanza. he initial letter design of this leaf persisted with little or no change for a long period, but the simple pendant spear was used as a distinctive motif for not more than twenty-five years. France: Hymnal. Illuminated. Early 14th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script; Gregorian notation.

-

-

Lectionary (Lectionarium)

-

A Lectionary contains selected readings from the Epistles and Gospels as well as the Acts of the Saints and the Lives of the Martyrs. These were read by the sub-deacon from a side pulpit. This practice necessitated that they be written in a separate volume, apart from the complete Missal. The fine large book hand shown here, suited to easier reading in a dark cathedral, is a revival of the script developed nearly four centuries earlier in scriptoria founded by Charlemagne. Maunde Thompson calls this Lombardic revival the finest of all European book hands. Even the 15th century humanistic scribes could not surpass it for beauty and legibility. The tone or hue of ink frequently helps allocate a manuscript to a particular district or century. Ink of brown tone is generally found in early manuscripts, less frequently after 1200 A.D. Italy: Lectionary: Middle 12th C. Latin text; Revived Carolingian script.

-

-

Livy's History of Rome (T. Livii ab Urbe Condita Libri)

-

The known part of Livy's great life work, the History of Rome, was completed about the year 9 A.D. The finished work consisted of one hundred and forty-two books, of which only thirty-five are extant. These books are regarded as one of the most precious remains of Latin literature. One of the outstanding characteristics of the scholars and scribes of the Italian Renaissance was their great interest in Latin literature. Through their influence, many copies of the classics were made from the few 9th and 10th century manuscripts available. These earlier manuscripts had been written in a carolingian or pre-gothic script to which the 15th century humanistic calligraphers assigned the name antiqua littera. The letters were not really of antiquity, since minuscule letters were not known before the time of Charlemagne. In the 15th century, this carolingian script became the inspiration not only for manuscripts like this leaf, but also, shortly thereafter, for the fine roman types designed by the printers in Italy. Italy: Livy's History of Rome (T. Livii ab Urbe Condita Libri). Middle 15th C. Latin text; Humanist script.

-

-

Missal (Missale Bellovacense)

-

This manuscript, a special gift to a church in the city of Beauvais, was written for Robert de Hangest, a canon, about 1285 A.D. At that time, Beauvais was one of the most important art centers in all Europe. The ornament in this leaf shows the first flowering of Gothic interest in nature. The formal heiratic treatment is here giving way to graceful naturalism. The ivy branch has put forth its first leaves in the history of ornament. The writing, likewise, is departing from its previous rigid character and displays an ornamental pliancy which harmonizes with the decorative initials. France (Beauvais): Missal (Missale bellovacense). Illuminated. Late 13th C. Latin text; Transitional Gothic script.

-

-

Missal (Missale Herbipolense)

-

The Missal has been for many centuries one of the most important liturgical books of the Roman Catholic Church. It contains all the directions, in rubrics and texts, necessary for the performance of the mass throughout the year. The text frequently varied considerably according to locality. This particular manuscript was written by Benedictine monks for the Parochial School of St. John the Baptist in Würzburg shortly after 1300 A.D. The musical notation is the rare type which is a transition between the early neumes and the later Gothic or horseshoe nail notation. The "C" line of the staff is indicated by that letter, and the "F" simply by a diamond, an unusual method. The bold initial letters in red and blue are "built up" letters; first the outlines were made with a quill and then afterward the areas were colored with a brush. Germany (Würzburg): Missal (Missale Herbipolense). Early 14th C. Latin text; Gothic script; transitional Early Gothic notation.

-

-

Missal (Missale Lemovicense Castrense)

-

The provenance of this manuscript is clearly designated as Limoges because of the inclusion of certain parts of the masses proper to this diocese, and because of the presence of the coat of arms and obituary records of the noted de Rupe family of that city. Frequently, without such data, it would be impossible to determine whether a fragment written in this period and country was from Amiens, Dijon, or Limoges. The national book hand had become amazingly uniform. In this manuscript as in many manuscripts of the 15th century there is an increasing tendency to speed and slackness. France was no longer setting the standard for manuscripts. This example shows that they were greatly influenced by contemporary Italian manuscripts. France (Limoges): Missal (Missale Lemovicense Castrense). Middle 15th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Missal (Missale Plenarium)

-

Many Missals, Bibles and Psalters of the 12th century were written in this fine, bold script. It was a revived form of the 9th century carolingian minuscule. In the absence of miniatures and decoration, it is difficult to assign a manuscript in this hand to a particular country. Some of the letters in this book, however, have been carefully compared with those in a manuscript known to have been ordered in Spain in 1189 A.D. by a certain Abbot Gutteruis, and it was found that the resemblance is striking. It is possible, therefore, that this leaf was written in the same monastery. However, because of the uniformity of all scripts in the early period, many English and French manuscripts could present close similarities in the style of writing. Spain (or Southern France): Missal (Missale Plenarium). Middle 12th C. Latin text; Revived Carolingian script.

-

-

Missal (Missale)

-

A Missal gives the service of the mass and is used by the clergy. The text is lengthy and in this large script would occupy many hundred pages. One wonders why this particular manuscript copy on vellum was written some forty years after Antonius Zarotus had printed the first Missal in Milan (1471 A.D.), for, at this time, Missals were frequently reprinted on paper and sold at only a fraction of the cost of a manuscript copy. This Bátarde style of semi-gothic script was the molding force for the fraktur and schwabacher type-faces which dominated German printing for several centuries. Germany: Missal. Early 16th C. Latin text; Lettre Bátarde.

-

-

Missal (Missale)

-

The Missal, written for the convenience of the priests, combined the separate books formerly used in different parts of the service; namely, the Oratorium, Lectionarium, Evangeliarium, Canon, and others. Gutenberg, who printed his famous First Bible about the time this manuscript was written, based his type designs on a contemporary book hand similar to this example. The craftsmen who created this manuscript had the difficult problem of evolving a harmonious page with two sizes of writing, inserted rubrics, and large and small colored initials. The smaller writing is used for the Orationes, the Psalms, the Secreta, and other parts of the service; the larger script for the Sequentia. Germany: Missal. Middle 15th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Missal (Missale)

-

The fact that this Missal honors particular saints by its calendar and litany indicates that it was made by friars of the Franciscan order. This was established in 1209 by St. Francis. These wandering friars with their humility, love of nature and men, and their joyous religious ferver, soon became one of the largest orders in Europe. This leaf, with its well written, pointed characters and decorative initial letters, has lost some of its pristine beauty, doubtless through occasional exposure to dampness over a period of 600 years. The green tone of the ink is more frequently found in English manuscripts than in French. However, the ornament and miniature on the opening page of the manuscript definitely indicate that it is of French origin. France (Rouen): Missal. Illuminated. Late 14th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

New Testament, with Glosses of Bede, Jerome, and Gregory (Testamentum Novum, cum Glossis Bedae, Hieronymi, et Gregorii )

-

The chief interest of this text is the interlinear glosses and commentaries from the writings of Bede, Jerome, Gregory, and other Church Fathers. These were inserted at various times during the following century around a central panel of the original text. All the hands are based on the revival of early carolingian minuscule. The beginning of the trend to compactness and angularity is seen in many of these later additions. This manuscript shows through marks of ownership that it was in Geneva for centuries. It is therefore probable that it was written in Switzerland. Switzerland (?): New Testament (Testamentum Novum, cum Glossis Bedae, Hieronymi, et Gregorii). Early 12th C. Latin text; Revived Carolingian script.

-

-

Oxford Bible (Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata)

-

It is usually difficult to dinstinguish the miniature or portable Bibles made by the young Dominican friars in England from those written in France. At times the colophon tells us that a book was executed in the Sorbonne, the newly founded school of theology in Paris, or in the University Center at Oxford. The Dominican order was founded in 1216 A.D. and soon spread all over Europe. About 1219 A.D., King Alexander of Scotland met St. Dominic in Paris and persuaded him to send some members of his brotherhood to Scotland. From here they spread to England. The original master text was carelessly transcribed again and again. It may even have been incorrectly copied from the Alcuinian text written for Charlemagne. Therefore, "correctories" had to be made. In the latter part of the 13th century, Roger Bacon condemned unsparingly manuscripts which, although they were skillfully and beautifully written, transmitted inaccuracies of text. England (Oxford): Oxford Bible. Middle 13th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Psalter (Psalterium)

-

Illuminated Psalters occur as early as the 8th century, and from the 9th to the beginning of the 14th century they predominate among illuminated manuscripts. About 1220 A.D., portable manuscript volumes supplanted the huge tomes favored in the preceding century. This change in size caused the creation of a more angular and compact script. In general, smaller initial letters were used, and writing was done in double columns. At this time the pendant tails of the initial letters are rigid or only slightly wavy, with a few leaves springing from the ends. Later, they became free scrolls, with luxurious foliage, and were extended into all the margins. The blue and lake (orange-red) color scheme with accents of white is a carry-over from the Westminister tradition which prevailed in the previous century. The solid line-filling ornaments at the ends of the verses were a new feature added in the second half of the 13th century. Silver and alloys of gold are used on this leaf. England: Psalter. Illuminated. Late 13th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

Pages