Fifty original leaves from medieval manuscripts

Pages

-

-

Antiphonal (Antiphonarium)

-

The chanting of hymns during ecclesiastical rites goes back to the beginning of Christian services. Antiphonal or responsive singing is said to have been introduced in the second century by St. Ignatius of Antioch. According to legend, he had a vision of a heavenly choir singing in honor of the Blessed Trinity in the responsive manner. Many of the more than four hundred antiphons which have survived the centuries are elaborate in their musical structure. They were sung in the medieval church by the first cantor and his assistants. Candle grease stains reveal that this small-sized antiphonal was doubtless carried in processions in dimly lighted cathedrals. In this example the notation is written on the four-line red staff which was in general use by the end of the 12th century. The script is the usual form of Italian rotunda with bold Lombardic initial letters. Italy: Antiphonal. Early 15th C. Latin text; Rotunda Gothic script; Gregorian notation.

-

-

Aurora

-

This famous paraphrase of the Bible in Latin verse was one of the most popular Latin books of poetry of the late 12th and 13th century. Petrus de Riga, who died in 1209, began it. Aegidius of Paris finished it. This version did not appear in printed form until a very late date, despite its popularity. The format of this page, twice as long as it is wide, demonstrates the English custom of folding the skins lengthwise. The practice of setting off by a space the initial letter of each line also helps to give the page an unusual appearance. It is written in a very small script, six lines to an inch, in a hand characteristic of Northern France and England at this period. England: Aurora. Early 13th C. Latin text; early Gothic Script.

-

-

Bible (Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata)

-

This copy of the Latin version by St. Jerome was made during the period when France stood at the height of her medieval glory. A decade or two before, Louis IX (Saint Louis), the strongest monarch of his age, had made France the mightiest power in Europe. This favorable political situation rendered possible the "golden age" of the manuscript, and Paris became the center in which the finest manuscripts were written and sold. rich opaque gouache pigments, with ultramarine made of powdered lapis lazuli predominating. The foliage scroll work inside the initial frame created a style that persisted with little or no change for nearly two hundred years. The script was well executed and was without rigidity or tension. All these elements, together with the sparkle which was created by the casual distribution of the burnished gold accents, give to this leaf a striking atmosphere of joyous freedom. France: Bible. Illuminated. Late 13th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Bible (Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata)

-

This translation of the Bible was made by Jerome at the request of Pope Damasus. It was begun in the year 382 A.D. and finished 16 years later. For his great scholarship more than for his eminent sanctity, Jerome was later made a saint. This version of the Bible was his most important work. The angular book hand, executed with amazing skill and precision, reflects the spirit of contemporary architecture of the early 13th century. Closely spaced perpendicular strokes and angular terminals have supplanted the open and round character of the preceding century. It is a beautiful book hand but exceedingly difficult to read. The quills used in writing were obtained from the wings of crows, wild geese, and eagles. To keep them sharp and their strokes of uniform width required skill and great sensitivity in hand pressure. It would be difficult to imitate or approximate the fine details even with the special steel lettering pens of today.

-

-

Bible (Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata)

-

In 1217, St. Dominic, the founder of the order which bears his name, withdrew from France and settled in Italy. Here, in the next four and last years of his life, he founded sixty more chapters of the Dominican order. Many of the younger members of the order studied at the University of Bologna and, while there, produced a great number of these small portable Bibles, just as did their brothers at the University of Paris in France and the University of Oxford in England. There was a difference in the art of the scriptoria in the various countries. In England and France the ideal of craftsmanship was very high, while at this time, in Italy, a rather casual attitude prevailed. In the 13th century, Italy was distraught by the long struggle between the papal and anti-imperialistic Guelphs and the autocratic and imperialistic Ghibellines. Little encouragement was given by either party to the arts. This leaf reveals, however, the skill and keen eyesight which were necessary for the writing of ten of these lines to the inch. Italy: Bible. Middle 13th C. Latin text; Rotunda Gothic script.

-

-

Bible (Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata)

-

The Vulgate Bible, a translation credited to St. Jerome, was adopted by the Catholic Church as the authorized version. This leaf was written in Germany nearly sixty years after the invention of printing by movable type. Its semi-gothic book hand is very similar to the type-faces used by the early printers. The numerous contractions and marks of abbreviation have been inserted boldly, but the little strokes which were added to help identify the letters "i" and "u" are barely visible. The new art of printing concerned itself at once with the printing of Bibles of folio size, in Latin as well as the vernacular. In Germany, prior to the discovery of America, twelve printed editions of the Bible appeared in the German language and many others in Latin. An oversupply developed, and more than one printer of Bibles was forced into bankruptcy. Germany: Bible. Late 15th C. Latin text; Semi-Gothic script.

-

-

Bible (Biblia Sacra Latina, Versio Vulgata)

-

These miniature or portable manuscript copies of the Jerome version of the Bible were nearly all written by the young wandering friars of the newly founded order of Dominicans. With almost superhuman skill and patience, and without the aid of eyeglasses, an amazing number of these small Bibles were produced by writing with quills on uterine vellum or rabbit skins. Many such Bibles were produced for students at the early medieval universities and were made in such large quantities that today they are easy to find. The precision and beauty of the text letters and initials executed in so small a scale, twelve lines to an inch, with letters less than one-sixteenth of an inch high, are among the wonders in book history. France (Paris): Bible. Middle 13th C. Latin text; Minuscule Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Book of Hours (Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis)

-

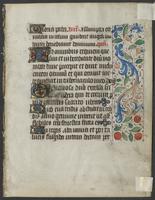

Books of Hours, beautifully written, enriched with burnished gold initials, and adorned with miniature paintings, were frequently the most treasured possessions of the devout and wealthy layman. They were not only carried to chapel but were often kept at the bedside at night. Oaths were sworn on them. Books of this small size, two and one-half by three and one-half inches, are comparatively rare. The craftsmanship in this example imitates and equals that in a volume of ordinary size, about five by seven inches. Recently these small "pocket" editions have been given the nickname "baby manuscripts." In general, the miniature Books of Hours contain only that section of the complete volume which deals with the prayers to be read or recited at the canonical hours; namely, matins, vespers, nocturns, and those for the prime, tierce, sext, nones, and complin. Indulgences were often granted for the faithful reading or recitation of these prayers. France: Book of Hours. Illuminated. Middle 15th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

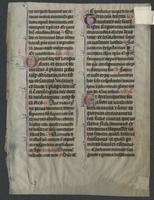

Book of Hours (Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis)

-

In the second half of the 15th century, the devout and wealthy laymen had a wide selection of Books of Hours from which to choose, both manuscript volumes and printed texts. These were often sold, in large cities, in book stalls erected directly in front of the main entrance to the cathedral. The first printed and illustrated Book of Hours appeared in 1486. It was a crude work, but later noted printers such as Verard, Du Pre, Pigouchet, and Kerver issued in great numbers Books of Hours with numerous illustrations and rich borders. The decorations were frequently hand colored and further embellished with touches of gold. These Books of Hours created a strong competition for the more costly manuscript copies. Customers who still preferred the manuscript format and could afford it also had a choice of may different types of decoration and could stipulate what quantity and quality of miniatures they desired. By this time the ivy spray had a variety of forms. It might be seen springing from an initial letter, from the end of a detached bar, in a separate panel in company with realistic flowers, or forming a three- or four-sided border intermixed with acanthus leaves and even birds, animals, and hybrid monsters which are neither man nor beast. France: Book of Hours. Middle 15th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Book of Hours (Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis)

-

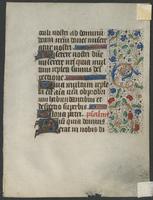

In the 15th century Books of Hours were as much in demand in the Netherlands as they were in France and England. In many of these books it is difficult to distinguish the Dutch Hours from those of Northern France or the Rhineland. In the middle of the century this whole area was interested in naturalism and made its illustrations so vivid that sometimes they approached those of our seed catalogues. It is not difficult to recognize carnations, pansies, columbines, and strawberries. The style later became even more realistic when the naturalistic flowers were painted with cast shadows. When such flowery decorations are found on a rather heavy piece of vellum, entangled with the swirling acanthus leaf and accompanied by a heavy lettre de forme script, one can be fairly safe in assigning the leaf to the province of Brabant. It was a difficult technical achievement at this time to apply the gouache colors to gold leaf so that they would adhere without flaking. Netherlands: Book of Hours. Illuminated. Late 15th C. Latin text; Lettre de Forme.

-

-

Book of Hours (Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis)

-

This particular Book of Hours, a devotional prayer book for the layman, was made for the use of Sarum, the early name for Salisbury, England. This text was accepted throughout the province of Canterbury. The manuscript was written about the time Chaucer completed his Canterbury Tales, but evidently by a French monk, who might have been attached, as was often the case, to an English monastery. Again, the book could have been specially ordered and imported from abroad. The initial letter and the coloring and the treatment of the ivy are unmistakably French. The lettering is an excellent example of the then current book hand. There are seven lines of writing to an inch. The words written in red, a heavy color made from mercury and sulphur, show almost the same degree of delicacy as those written with the more fluid ink. England: Book of Hours. Illuminated. Middle 14th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Book of Hours (Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis)

-

The text of a Book of Hours consists of Gospels of the Nativity, prayers for the Canonical Hours, the Penitential Psalms, the Litany, and other prayers. The beauty of the rich borders found in some of these books frequently claims our attention more than the text. In these borders it is easy to recognize the ivy leaf and the holly, but is usually more difficult to identify the daisy, thistle, cornbottle, and wild stock. The monks had no hesitancy in letting these flowers grow from a common stem. Because of the translucency of vellum, the flowers, stems, and leaves of the border were carefully superimposed on the reverse side in order to avoid a blurred effect. France: Book of Hours. Middle 15th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Book of Hours (Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis)

-

It is generally no great task to assign these illuminated Books of Hours to a particular country or period. The treatment of the ivy spray with the single line stem and rather sparse foliage is characteristic of the work of the French monastic scribes about the year 1450 A.D. The occasional appearance of the strawberry indicates that the illuminating was done by a Benedictine monk. Fifty years earlier the stem would have been wider and colored, and the foliage rich; fifty years later the ivy and holly leaves would be entangled with flowers and acanthus foliage. France: Book of Hours. Illuminated. Middle 15th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Book of Hours (Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis)

-

This Book of Hours shows definite characteristics of the manuscript art of France and the Netherlands of about 1450 A.D. It was probably one of many copies prepared for sale at a shrine to which devout pilgrims came to worship or to seek a cure. The spiked letters and the detached ornamental bar are unmistakably Flemish in spirit, while the free ivy sprays are distinctively French. The burnished metal in the decorations shows the use of alloyed gold (oro di meta) as well as silver. Various metals were added in different localities to the fine gold. English illuminations frequently had a decided orange hue, while the French had a lemon cast. The quality of the gold was best enhanced by the use of burnishing tools equipped with an emerald, a topaz, or a ruby. Less successful burnishers contained an agate or the tooth of a wolf, a horse, or a dog. Northern France: Book of Hours. Illuminated. Middle 15th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Book of Hours (Horæ Beatæ Mariæ Virginis)

-

In assigning this leaf from a Book of Hours to the Netherlands it must be remembered that some sections of that country were once part of France, while others belonged to what is now Germany. In this leaf French characteristics predominate, but in no other country did the study of nature have a more direct influence on miniatures and ornamentations that in the Netherlands. Carnations, pansies, columbines, and many other flowers were faultlessly and realistically drawn. A few decades later, at the turn of the century, cast shadows as well as snails, butterflies, and birds were added, with the result that the borders became a distraction to the reader. Netherlands: Book of Hours. Illuminated. Late 15th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Book of Hours (Horæ Beatæ Mariæ Virginis)

-

The Book of Hours, the prayer book of laity, usually contains 16 sections. The section on prayers to the Virgin is the most important and most used, and its manuscripts exceed in number all other 15th century religious texts. The laymen who ordered and purchased these books would at times stipulate the style of ornament and the amount of burnished gold to be used, and could even, to a certain extent, select the saints they esteemed most and wished to glorify. In this example, the border reveals by its wayside flowers entangled with the heavy acanthus motif of the North and by the use of "wash" gold that it was executed in Northern France about 1475 A.D. Northern France: Book of Hours. Illuminated. Late 15th C. Latin text; Gothic script.

-

-

Book of Hours (Horæ Beatæ Mariæ Virginis)

-

This manuscript leaf came from a Book of Hours, sold probably at one of the famous shrines to which wealthy laymen made pilgrimages. To meet the demand for these books, the monastic as well as the secular scribes produced them in great numbers. The freely drawn, indefinite buds here entirely supplant the ivy, fruits, and realistic wayside flowers which characterized the borders of manuscripts of the preceding half century. The initial letters of burnished gold on a background of old rose and blue with delicate white line decorations maintain the tradition of the earlier period. The vellum is of silk-like quality that often distinguished the manuscripts of France and Italy. France: Book of Hours. Illuminated. Late 15th C. Latin text; Gothic script.

-

-

Book of Hours (Horæ Beatæ Mariæ Virginis)

-

This beautiful manuscript leaf was written and illuminated about the year 1535 A.D. At this late date Books of Hours were also being printed in great numbers by such famous French printers as Vostre, de Colines, and Tory. These were elaborately illustrated and frequenly hand-colored. The cursive gothic script used in this leaf, with its boldly accented letters and flourished initials, borrowed heavily from the decorative chancery or legal hands of the 13th and 14th centuries. It influenced the type face known as civilite, designed by Granjon, and first used in 1559 A.D. France: Book of Hours. Illuminated. Early 16th C. Latin text; Cursive Gothic script.

-

-

Book of Hours (Horæ Beatæ Mariæ Virginis)

-

In general, the Books of Hours produced for the devout layman in the Netherlands at the end of the 15th century were written in Dutch. This particular example, however, is in Latin. The heavy, angular, and closely spaced vertical strokes, with very short ascenders and descenders, give a much darker tone to the page than to similar scripts in such northern countries as Germany and England. This book hand resembles very closely the types known as lettre de forme which were used by certain anonymous contemporary printers in the Netherlands between 1470 and 1500 A.D. Netherlands: Book of Hours. Late 15th C. Latin text; Bold Angular Gothic script.

-

-

Breviary (Breviarium)

-

The Breviary is one of the six official books used by the Roman Catholic Church in its liturgy. It is a book of prayer for the clergy, giving the directions for all of the various services of the Divine Hours throughout the year. The other five official books are the Pontifical, the Missal, the Ritual, the Martyrology, and the Ceremonial of the Bishops. The angular script in this leaf is executed with great skill and precision. The small and vigorous black initials and the hair line details found in many of the ascenders and terminal letters indicate the work of a superior calligrapher, skilled not only in writing but also in sharpening his quill. The initials and the dorsal decorations also represent the same high standard of craftsmanship. Strangely, the rubrications do not show as great a calligraphic skill. Usually it was the task of a superior scribe to insert the rubrics or directions for conducting the service. France: Breviary. Late 13th C. Latin text; Angular Gothic script.

Pages